by Paidamoyo Chipunza Senior Health Reporter for The Herald

Back in 1981, heavily pregnant Mary Maropa (not her real name) left her village in Nkayi for hospital expecting to return with a baby. Little did she know that she will not only return with tears on her cheeks but also uncontrollably leaking urine from her vagina, a medical condition known as vesicovaginal fistula (VVF). Due to prolonged labour pains coupled with complications during delivery, Mrs

Maropa lost both her unborn baby and her dignity.VVF occurs when a woman struggles with labour for days without giving birth with the pressure of the baby’s head cutting off blood supply to delicate tissues causing a hole to form between the birth canal and the bladder. It is this hole that urine leaks from uncontrollably.

“From this day, I started wearing sanitary pads all my life because I could not control my bladder anymore,” said Mrs Maropa.

“Although my husband did not leave me because of my condition, it was so embarrassing to talk about it to any other person or being around other people because people would talk about the stink of urine around them,” she said.

Mrs Maropa said even with vaginal fistula, she went on to deliver three more children now aged 22, 20 and 18 years but all the nurses who attended to her professed ignorance on the condition or at least referring her to where she can get medical assistance.

“I had lost all hope and was thinking this condition was for life. I was stinking urine most of the time."

Thirty-five years down the line, Mrs Maropa said she heard a programme on radio on the burden of obstetric fistulas in Zimbabwe and planned repair camps slatted for Chinhoyi Provincial Hospital and decided to approach the health facility.

Mrs Maropa joins 86 other women from different parts of Zimbabwe with similar and worse conditions who have successfully undergone corrective surgery at the Chinhoyi Provincial Hospital. They are beneficiaries of a Government programme aimed at ending fistulas in Zimbabwe.

In the fistula camp, also there is 18year old Mrs Mary Muzadzi (not her real name) from Chipinge with two types of fistulas — vaginal and rectal.

Factors that lead to vaginal fistula are the same that lead to rectal fistula, but this time the hole is formed between the birth canal and the rectum. Mrs Muzadzi has both vaginal and rectal fistula meaning she leaks both urine and stool through her vagina.

She said she tried to deliver from home because of the distance from her village to the nearest clinic but she failed.

On day three, Mrs Muzadzi said, she was ferried to the clinic in a scotch cart where she had a stillbirth through caesarian section. She had already suffered a vaginal and rectal fistula.

“This happened in April last year and since then we have stopped sexual intercourse with my husband. The pregnancy that led to this abnormality was my first, so I was actually contemplating going back to my parent’s home before I heard of the repairs at this hospital,” she said.

Obstetric fistulas are not peculiar to Mrs Muzadzi and Mrs Maropa as 500 other women from different parts of the country with similar conditions are currently awaiting the corrective surgeries.

Women and Health Alliance (WAHA) representative Dr Michael Wolde Ambaye whose organisation is conducting the surgeries with assistance from local surgeons said there was no reason for women with

obstetric fistulas to continue leaving with the disability.

“Obstetric fistula is preventable but on top of that it can be treated. For the operations we have done so far, we have seen a 96 percent success rate,” she said.

Dr Ambaye said of the 86 success stories, 80 women had vaginal fistula, five women had rectal fistula while five others had both vaginal and rectal fistula. She said four operations were deemed not fit for operations. Dr Ambaye is working with another expatriate doctor, six doctors from Harare and Bulawayo hospitals, two more doctors from Chinhoyi hospital and several other health workers. “This is meant to share skills with local health workers to ensure continuity and sustainability of the programme when we leave Zimbabwe,” she said.

UNFPA country representative Mr Cheikh Tidiane Cisse said efforts towards ending obstetric fistulas in Zimbabwe started in 2009 with a survey to establish the actual burden of the condition among women. In September 2015, Government in partnership with the UNFPA and WAHA, conducted its first ever fistula repair camp where 30 women were operated on. The second camp was done in November and December 2015 and the third camp opened last week and will run until May.

“The response for both camps was overwhelming, and we have 500 women currently on the waiting list. This clearly shows that there is a gap in treatment for women with fistula,” said Mr Cisse.

Mr Cisse commended Government for embracing the initiative saying majority of the affected where often poor and cannot afford this corrective surgery.

“We have heard how this condition can rob women of their dignity and status in society, rob them of their source of livelihoods by forcing them to be confined to the back of their homes and leave them ostracised and humiliated,” said Mr Cisse.

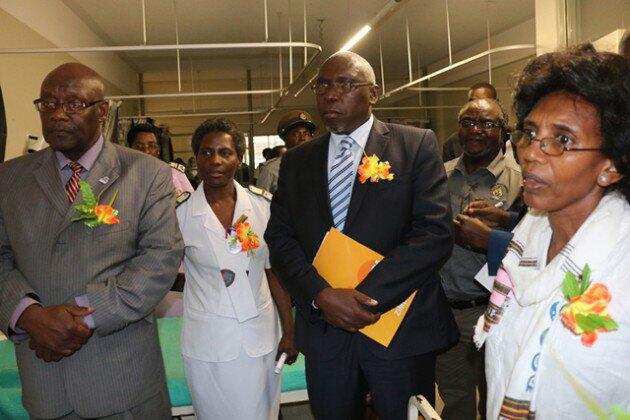

Health and Child Care Minister Dr David Parirenyatwa commended Chinhoyi Hospital for taking up the challenge in ending fistulas thereby becoming the centre of obstetric fistula repairs in Zimbabwe. Locally, fistula repairs are only done at Chinhoyi Hospital.

Dr Parirenyatwa said although Government was looking forward to conduct more fistula camps, it was also planning to set up a fistula treatment site at United Bulawayo Hospitals to cater for women from the southern region. He said Government did not want the programme to end with camps but was looking at sustainability of the programme and do not want it to end with camps.

“We need to make a difference in women, we will continue to mobilise funds for this programme not

only for it to be sustainable but to be of high quality, said Dr Parirenyatwa.

He said Government is also going to develop a five year action plan for obstetric fistula programme and an advocacy and communication plan to effectively tackle the problem in Zimbabwe. Dr Parirenyatwa called on women who might be living with the condition to seek medical assistance urgently to avoid developing other complications.

“Left untreated, obstetric fistula causes chronic incontinence and can lead to a range of other physical ailments including frequent infections, kidney disease and infertility. It can lead to social isolation and psychological harm to the affected women,” he said.

He said to prevent obstetric fistulas, women must deliver under supervision from a trained midwife in a

health facility.

Obstetric fistula is one of the most serious and tragic injuries that can occur during child birth. According to UNFPA, obstetric fistula affects over 2 million women and girls worldwide and between 50 000 and 100 000 new cases develop each year. Although the actual burden is not known in Zimbabwe, the Government survey conducted in 2009 showed that at least 88 women with the condition were seen at central, provincial and district hospitals in 12 months preceding the survey.